All Posts

- Pedro Pontes

- Jun 26, 2015

- 3 min read

That the glass thickness and distributions are paramount for a glass container is a statement that comes without question. But most probably we’ve found situations where a container is within the specifications and still breakages occur.

This article will explore a real case situation, where it was requested to Empakglass to evaluate the design of a 750ml bottle, which has a consistent glass thickness and distribution and nevertheless, breakages did occur when internal pressure load was applied.

For the simulations presented on this article, the Empakglass Forming Software was used (Empaktor Suite).

The method applied by Empakglass consisted on the following:

The client provided the current bottles in order to make cuts to determine the glass distribution;

The client provided the glass composition and gob temperature;

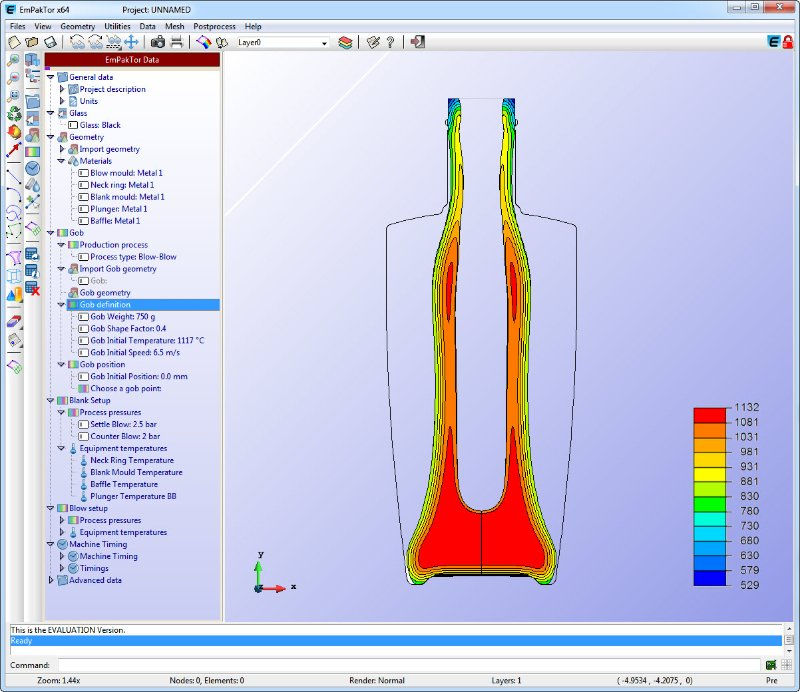

The current client’s parison design was simulated using Empakglass’s Forming Software and based on the physical properties of the used glass and the client’s IS machine timing;

A comparison between the real current glass thickness distribution and the one achieved by the simulation was performed. Although there was still a deviation on the settle wave line position It was verified that the achieved simulation profile was quite similar to the actual bottles,

Using the achieved wall thickness profile, a stress analysis for internal pressure load was performed on the model to assess the resistance of the current bottle design.

Following the principle that failure only occurs when generated stresses exceeds the glass strength, all the maximum surface stress values achieved on the above shown Internal pressure simulations are below the glass strength limits, meaningthis design is theoretically acceptable for beverage usage with a Carbonatation of 4Vol-CO and for pasteurization at 70°C.

Nevertheless and although the simulation results theoretically pass the bottle design, a pattern between the breakage origin and the simulation can be determined.

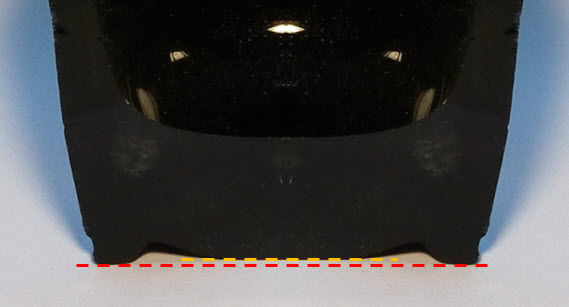

The sidewall area of a bottle is one of the identified critical areas of a container in what regards its resistance to internal pressure. The type of breakage shown on the above pictures has undoubtedly a sidewall origin (settle wave area).

On this particular bottle the settle wave line (associated with lower wall thickness values) is placed on the contact area of the bottle.

Due to the production process limitations (B&B), to have an absolute control on the thickness values achieved on the settle wave area during production is statistically low and therefore will generate bottles that will fail under the tests performed by QC.

The parison design is without any doubt one of the main tools where a glass producer can try to compensate the lack of glass on the settle wave area.

In order to prove the relation between the wall thickness values and the internal pressure resistance, a new parison was developed and again simulated. This parison used the same glass weight. As well, the new parison was also shorter in order to compensate the fast rundown seen on the forming simulations

The forming simulation results show that on the new developed parison, a higher wall thickness on the settle wave area has allowed to shift the weakest area on the container from a glass contact area to a non-contact area on the shoulder.

By increasing 0.55mm on the settle wave area (see figure 4), there was an increase of extra 15% resistance to the internal pressure load even by keeping the same glass weight.

Also, complementing the proper mould design and having in mind that it is critical to protect the surface areas against surface abuse, especially in the contact points, where the probability is higher of having any kind of abuse.

By achieving this is by having good Hot End Coating (HEC) and Cold End Coating (CEC) application. The combination of these two coatings protects the glass surface against friction damage. This damage typically occurs when a blunt hard object slid across a glass surface – for example – two bottles slid against each other in manufacturing line and filling line. Resistance to scratching must be achieved so as to keep the inherent bottle strength high.

For HEC – for carbonated bottles – the level should between 30 to 40 CTU and 25 CTU should be the absolute minimum. It should be guaranteed an even distribution of the coating throughout the glass surface.

For CEC the recommend values are between 9 to 12 degrees of slip angle (determined with AGR Tilt Table). Again, it should be guaranteed an even distribution of the coating throughout the glass surface.

So, summoning this article:

We can have a bottle with a reasonable glass thickness and distribution;

The glass distribution is within Quality AQL’s for that particular container;

Nevertheless, the container fails under internal pressure loads;

By developing a new parison and keeping the same glass weight on this container, it is possible to shift the weakest area on the container from the labeling area (glass contact area) to the shoulder (non contact area).

- Hélder Remédios

- Jun 23, 2015

- 4 min read

It isn’t the most common issue to find in a glass plant. However for niche markets - where the same bottle or jar is produced in different colors, this becomes something to have in consideration technical wise. The end results will be significantly different and commercial wise has implications when budgeting the costs of a production.

On this article we will show a practical case, where for the same mold design, very different results were achieved in terms of glass distribution. Glass distribution is, without debate, the most important contributor for the integrity of any glass container. The simulations here shown were made using Empakglass’s Forming Software.

Glass color in terms of physical properties directly influences the thermal transmission. This is common sense: we know how sun light crosses more or less along a lighter or darker window.

On a IS machine, the reheating time, which is part of the production process is directly influenced by the thermal conductivity of glass.

The reheating is the period of time between the end of the parison transfer and the start of the final blow. During this time, the parison tends for temperature equalization (reheat) and gravity stretches it. Excessive reheating on the blank mold side allows the parison to sag and on the blow side to run, and the two effects have to be counterbalanced. Stretching and cooling of the parison can be helped by the use of overhead cooling over the blow mold.

The speed of invert affects the glass distribution of the finished bottle: if it is too slow, the parison will sag backward due to gravity; if too fast, the parison is thrown forward by centrifugal force. The speed must be varied to suit the weight, viscosity and shape of parison.

Coming back into the glass physical properties. When comparing a darker glass versus a lighter color glass, the time to equalize the parison temperature will take longer on the first case. Therefore the sag/run effects will be less for the same actual time cycle comes to place.

For this particular case study example, the blank molds were developed for a Empakglass client flint glass. The consistency of the Forming Simulation results was confirmed in the actual bottle production.

(images from left to right: Glass thickness simulation ;3D Rendering; Actual bottle)

When the client decided to use the same mold set with “black” color glass, a visual defect appeared around the heel area. A “wave” shape, with a “cold” appearance and the heel region wasn’t completely formed.

(images from left to right: Wave shape defect and heel region not completely formedly formed)

Another defect that was detected were “dropped bottoms”. These did not appear in the flint bottles produced with the same mold set.

This defect is consistent with temperatures higher than the softening point (log 7.65).

Curiously, although this might have two different reasons (cold appearance and dropped bottoms), the root cause is just one – the thermal conductivity of black glass.

By using Empakglass’s Forming Software and simulating in black and comparing with flint, :

the glass outside surface temperature on the moment where the final blow starts has an average of 40 degrees lower in black color when compared with flint => cold appearance on the out surface and "wave" look;

The isotherm areas above 1080ºC in black glass are bigger than in flint, mainly around the shoulder and mostly on the bottom, where the glass thickness is higher => longer to equalize temperature and therefore the occurrence of dropped bottoms already on the annealing lehr;

This is already showing that the black glass reheat time is too slow when compared with the flint (more difficult to have thermal transmission).

(image above shows client's Flint Glass thermal profile)

(image above shows client's Black Glass thermal profile - forming simulation)

In practice, this means that in “black” when the final blow is applied, the glass is still cold on the outer surface and will not form completely on the blow side.

This confirms as well the practice from Production Staff when it states that with darker colors and the higher the thickness the worse it will be in terms of reheat time.

The excessive glass thickness on the bottom together with the reheat time difference between flint and black is too big (almost double). In black glass we can see a deformation on the bottle heel, that doesn’t appear in flint, already after the bottles entered the annealing lehr.

(image on the left shows the temperature/glass thickness profile using black glass physical properties and image on the right the actual bottle)

In black, due to the thermal conductivity, when comparing with flint glass it is required to reduce the bottle bottom thickness to get a faster reheat time on the glass. This can be achieved by developing a different parison design, with higher overcapacity.

By doing so, both the “wave” look appearance on the heel and also the dropped bottoms effect can be solved.

(image above shows the comparison between the glass distribution for flint (in blue), with a blank mould with 25% overcapacity and a 40% overcapacity blank mould for black glass (in black) keeping the same weight)

Therefore this is one of the actual practical cases, where by keeping the same weight and increasing the overcapacity, a lower thickness on the bottom is achieved, in order to solve the issues presented above.

![EMPAKGLASS_-_510381600_-_Selo_TOP5_2025[1].png](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/3d4fdc_3232bb1b975e47d9b861a1b84575703f~mv2.png/v1/fill/w_175,h_175,al_c,q_85,usm_0.66_1.00_0.01,enc_avif,quality_auto/EMPAKGLASS_-_510381600_-_Selo_TOP5_2025%5B1%5D.png)